As a user experience designer or product designer, you’re constantly grappling with the task of testing a concept. But do you know what it really takes to become an expert at this?

Starting From Square One: What is a ‘Concept’, Exactly?

To master the process of building a proof of concept, it’s important that you first understand how ‘concept’ is defined:

“A concept consists of a speculation about the resolution of a product, a project or a feature.”

We can say that if a concept is a speculation of a resolution, we have to test our “hypothesis” and see if our speculation is valid or not. We can also say that nobody in their right mind would build something based entirely on speculation! Ryan Medeiros (Director, School of Web Design & New Media, Academy of Art University, San Francisco, USA) makes a more than accurate analogy when talking about Proof of Concept (PoCs):

“Like buildings and cities, interactive experiences need planning and a clear process for execution. And in the same way buildings need blueprints, mobile apps need a Proof of Concept.”

Ryan Medeiros focuses solely on mobile apps in his analogy but we can widen the scope for our purposes. Proofs of concept apply not only to mobile apps but also to a wide spectrum of interactive digital experiences.

Asking the Right Questions

To understand whether a concept can be (or should be) tested, we can ask a series of questions. Some of these questions, such as the following, are related to timing:

- How can I validate this concept in a fast and effective way?

- In what parts of the process can I save time?

Next, I’ll show you some techniques that we use here at Making Sense in order to optimize time in a PoC and obtain the desired results for both the client and the team.

Use Provisional Personas, Not User Personas

When it comes to testing a concept, one technique we use is the creation of Provisional Personas. What are they? Basically, they are a representation of the people who, if we met them on the street and we talked with them a few minutes, we would say with certainty that they would buy our product.

A Provisional Persona is a person created using historical, anecdotal, or statistical knowledge about a certain type of user, but is not based directly on patterns seen in user research. These “provisional people” or “proto-people” are built from stakeholder interviews in which we extract the facts, problems, behaviors, needs and objectives of the users that help us build this “provisional person”. This tool saves us a lot of time.

It should be remembered that proto-people should be used with caution and NEVER considered definitive users.

After this stage of the PoC process, we will have time to develop users validated by our exhaustive research, but for now, some quick-and-dirty research will be more than useful.

Provisional Personas are enough to guide the proof of concept

Task-based (goal-based)scenarios. Short and Concise

According to Usability, “Scenarios describe the stories and context behind why a specific user or user group comes to your site.”

The scenarios should have no more than 5 sentences and should describe a background story and a time/space context and the reason why the user considers using our feature, application or other types of products/services.

The creation of these scenarios is expedited if you work as a team. In order to generate an acceptable number of scenarios (between 10 and 30), it is better to have 2-3 team members who understand the users and the business. It should be noted that it is impossible to cover all the scenarios but with this exercise, the most important ones are contemplated (i.e. those that have to do with the nature of the application).

Fidelity of the Prototype

The fidelity of the prototype is KEY to being able to speed up the process during a proof of concept. I have seen user experience designers trying to reach a high level of fidelity of prototypes based on little more than aesthetic reasons. The degree of fidelity will vary. It is not the same an internal proof of concept to a PoC to obtain the buy-in the c-levels (chiefs).

One tip here is to understand that usability or aesthetics is not being tested. Rather, an idea is being put to the test. This goes far beyond the beautiful or ugly, or how usable or not usable it ends up being. The proof of concept will tell us HOW the product operates within this interactive project. For the aesthetic, we simply apply the best standards or usability guidelines that we have at the time.

I’m not saying that you always have to build low loyalty prototypes. I aim to have an awareness of defining each scenario without wasting time in medium or high fidelity prototypes when the minimum a low-fidelity version could suffice.

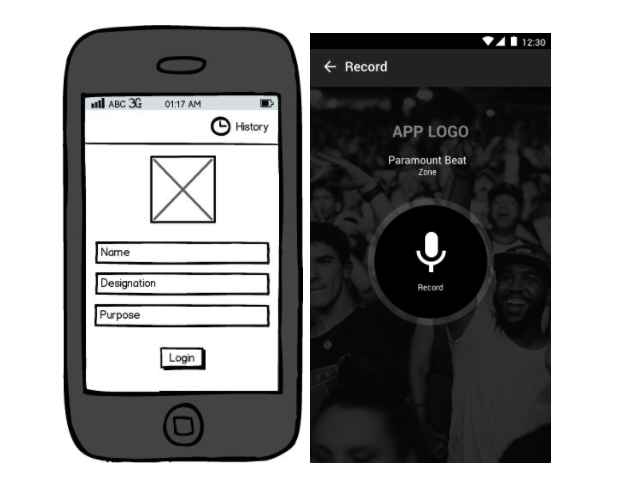

The difference between two types of wireframes is this: on the left, there is a low-fidelity wireframe and on the right, there’s a half fidelity. Clearly, you can see how the one on the right takes more time to create because more details are put into the design.

Low-fidelity wireframe Vs. Half-fidelity wireframe

Think of Lean UX

When you create a proof of concept and you want to speed up the times, it’s good to think about ‘Lean UX’. Here’s how Jeff Gothelf, UX Designer, define ‘Lean UX’:

“Inspired by Lean and Agile development theories, Lean UX is the practice of bringing the true nature of our work to light faster, with less emphasis on deliverables and greater focus on the current experience being designed.”

During the development of PoCs, you can focus on prototyping one or two of the main user flows. The documentation and the deliverables pass to the second level in order to be able to dedicate time to what is important at this stage, to validate the concept. Following this methodology, a prototype is set up as soon as possible in front of the users so that they can test. Since we are talking about testing, doing it with 5 users (as Jakob Nielsen recommends) will give us reliable results and allow us to maintain better control of our budget.

—

There is one factor that helps speed up a proof of concept which was not mentioned above. That factor is experience. Experience will allow this process to be carried out with greater efficiency, but unfortunately it cannot be taught. It is simply acquired over time.

At the end of a Proof of Concept process, the team should have a complete understanding of the results and should be able to clearly evaluate the viability of the initiative. As a result, deliverables are delivered (evaluation, prototype, documentation, etc.) as are the recommendations made during the proof of concept process.

These tools (and some others) and ways of thinking allow us to speed up the process of validation of proofs of concept. They also allow us to put, as soon as possible, a visualization of the idea to test in front of the users, the team and the client. I always like to emphasize the fact that a proof of concept must be maintained as such, not believing for a moment that it is going to be our final product or anything similar to it. Optimizing times is key because in the world we live in, time equals money.